Escape mode a forgotten feature.

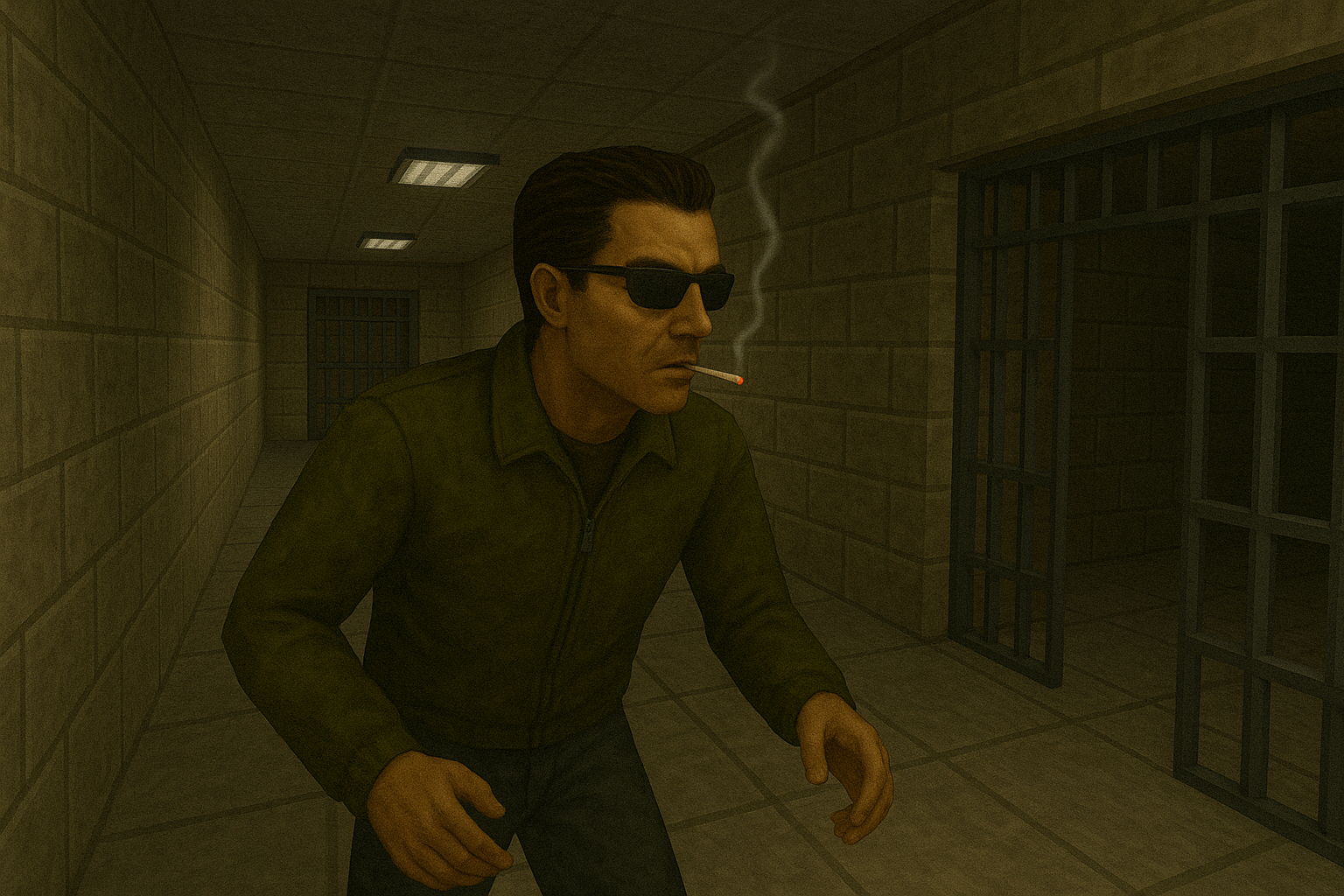

Note, this image is AI generated.

Hello everybody, it’s me, Slade Krowley.

Today I want to dust off a part of Counter-Strike’s history that most people have forgotten—if they ever knew it existed at all. Escape mode. Or just “es,” if you remember the old map prefixes.

Now, strictly speaking, it was never removed. The files are still buried in the game, as functional today as they were twenty-five years ago. What happened is simpler, and sadder: the mode was dropped early, cut off before Counter-Strike had even found its voice. By Beta 7.0, Escape was gone, and the game we know today—bombsites and hostages—became the whole show.

Some of you might recognize a few of the names: es_jail, es_frantic, es_trinity. These were the strange little experiments that carried the idea forward. Not many maps, not much polish. But the concept was there. And I’d argue it deserved more than the quick burial it got.

Here’s the premise: Terrorists had to reach an exit before the clock ran out. The Counter-Terrorists had to stop them. Simple. The twist was that Ts didn’t spawn with a buy zone. They had to scrape together weapons—either by scavenging from the map itself or from the corpses of dead players. It tilted the balance toward the CT side, the same way Assassination tilted against the VIP. Was it fair? Not really. Was it interesting? Absolutely.

And here’s where my mind wanders a little. The Half-Life engine, even back in 1999, could do things Counter-Strike rarely touched. Moving platforms. Breakable walls. Lights that flickered or blew out. Imagine Escape maps built around those possibilities. Not static corridors, but dynamic environments—a prison riot with gates failing in sequence, or a mountain base where the cable car is your only way out. Escape could have been Counter-Strike’s chance to show that a match didn’t have to be a static duel.

Modern CS2 mechanics actually fix a lot of the headaches Escape used to have. Volumetric smokes, for example, make scavenged grenades genuinely useful instead of just decorative. The improved physics and interactive scripting let exits feel alive—locked behind objectives, tucked behind destructible doors, or hidden in branching shortcuts. No more “CT camping every choke” and calling it a day.

The economy can finally be tuned properly. Terrorists get just enough cash for pistols or SMGs, while Counter-Terrorists have to make real choices before decking themselves out completely. And that scuttle mechanic? It turns the pre-round into its own little mind game—CTs plotting, Ts guessing, everyone on edge. It’s subtle, but it changes everything.

If someone rebuilt it today, I think the economy would need rewriting. Terrorists shouldn’t spawn helpless, but they also shouldn’t have AKs on tap. Give them a small stipend—enough for pistols or cheap SMGs. Place “black market” buy zones deeper in the map. That way, the scavenger energy stays intact, but they’re not cannon fodder. On the other side, Counter-Terrorists could stand to have a thinner wallet. Make them choose their choke points carefully instead of drowning every corridor in rifles and grenades.

Think about the “black markets” in Escape. They could hold more than just guns—things that bend the rules a little, make the mode feel different. Heavy body armor, for example, could let a player tank damage the way the VIP does in Assassination. Or stimpacks: quick injections to restore health, but only if you’re willing to stand still for a moment and risk it.

There’s room for stranger tools, too. Night vision goggles for dark corners. A kind of sonar that pings CTs who camp in one spot too long. Even weapons that wouldn’t belong in a standard defusal map—claymores for CTs, or the old CS gas grenade from Counter-Strike’s beta. Imagine that with CS2’s volumetric effects: a cloud rolling through a hallway, not just a texture but something alive, shifting.

The point is, Escape opens up space for experimentation. Things the main modes can’t or won’t touch. And with today’s tech, most of it wouldn’t be difficult to pull off. The possibilities are right there, waiting.

Map design is where it gets exciting. Imagine three escape points—a helipad, a loading dock, a boat at the pier. At the start of the round, CTs scuttle one of them, making it unusable. Sometimes the Terrorists would know which exit is gone; sometimes they’d have to scout it out. Either way, it turns into a chase. The Ts scrambling forward, gambling on routes, improvising. The CTs anticipating, cutting off, never able to cover everything.

The win condition could be as simple as this: half the Terrorist team escapes, and they win the round. That keeps the tension balanced on a knife edge—every survivor matters. Lose one more body than you can afford, and suddenly the whole plan collapses.

Done right, a modern Escape mode wouldn’t just feel like Counter-Strike with different doors. It would feel like a prison break. Or a heist gone sideways. The Terrorists are desperate and under-equipped; the CTs have control but limited firepower; and the map itself—its doors, shortcuts, destructible walls—becomes as important as any rifle.

And that, to me, is the real loss of Escape. Not that it was cut, but that it was cut before it had the chance to grow. It showed a path Counter-Strike could have taken—one where the game leaned harder into asymmetry, tension, and improvisation. Maybe someday it gets another shot.

Written by Slade Krowley. And remember: my friends, the dawn is your enemy.